This post contains my very early thinking about something that has intrigued me for a while: how we might take what we know about the application of pressure or force to various physical systems and relate it to our thinking about humans in change.

Loading

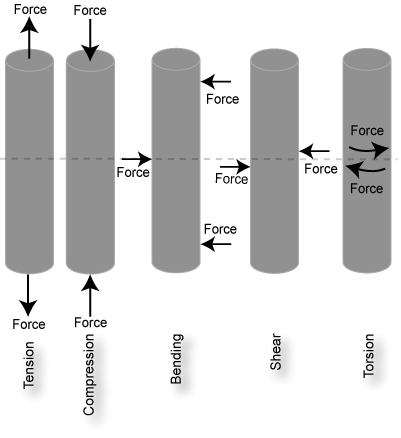

The application of force to an object is known as loading. Engineers study five different types of loading and their impact on structural systems. Here’s a diagram.

We know that when structural systems are overloaded, they can bend, break, deform, or collapse. As I started thinking about this, it occurred to me that many of the things people experience during change bear a relationship to one or more of these load patterns. When the load becomes too great, it’s not uncommon for people to describe themselves as feeling pulled apart, smashed, bent, broken, or twisted.

Bones

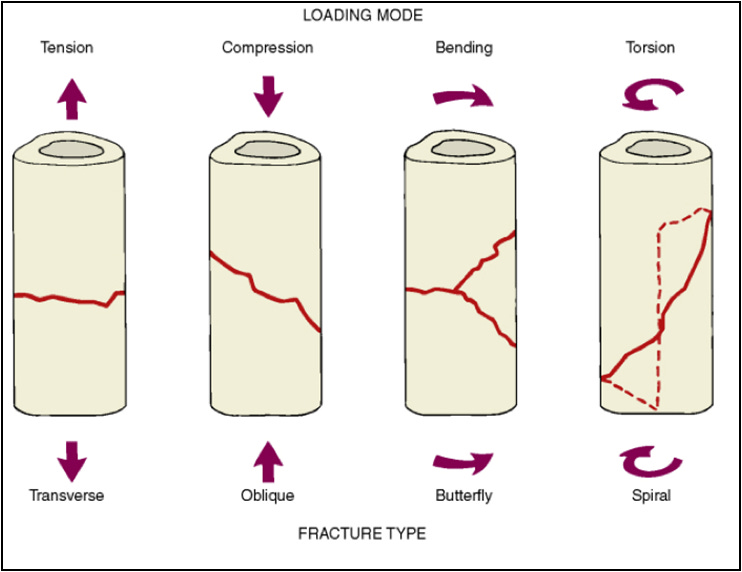

I find the application of this thinking to human bones to be particularly interesting. Here’s an interesting image that links different types of fractures to the “loading mode” that caused them.

I’ve stopped thinking of my meandering paths as “rabbit holes” and started calling them “curiosity paths.” This certainly took me on a journey! Here are a few interesting resources I found if you’re interested in digging a little deeper.1

Too Much, Not Enough, Just Right

Too much force can break buildings and bones. Too much pressure can break people as well. But underloading a system is not a good thing either. Bones need to bear weight to grow strong. Compression and bending stimulate cells that build bone mass, and also increase muscular strength for balance and fall prevention.

Likewise, humans need challenge to stimulate learning and productivity. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described the importance of balance between the challenge of a task and the skill of the performer in creating a sense of “flow;” the challenges created by organizational change give human systems an opportunity to accomplish meaningful goals.

Change Load

All of this got me thinking about the ways in which the various types of load might show up in the human experience of changes, and what it might feel like when these forces are very strong.

Tension

In the world of structural engineering, tension involves opposing forces pulling an object apart. Inside, molecules are trying to stay together and keep from being separated.

Changes create tension when they introduce objectives and goals, and areas of focus, that compete for attention with ones that are already in place, or when they include priorities that are incompatible and require making tradeoffs. This can create an experience of being stretched between two opposing forces.

Here are some things that might increase tension:

working for more than one function or boss, with differing priorities competing for time, energy, and attention

trying to attend to both work and family issues while working remotely

having a spouse or partner who would like you to spend less time working and a job that requires lots of attention

experiencing a conflict between your personal values and priorities and those that are most important to the organization

At a moderate level of force, the stretch of tension can be exhilarating. We build strength in negotiating, setting priorities, and clarifying our own purpose. At high levels, we may feel torn, conflicted, or pulled apart.

Compression

Compression involves opposing forces pushing on an object. Inside, molecules are pushing back, trying to stay apart and not get crushed.

Changes create compression when they introduce additional demands, requirements, or expectations that increase the load on an individual. Here are some things that might lead people to feel compressed:

responding to increased productivity requirements—needing to get more done with the same amount of time and resources, or to do the same work in less time

taking on added family responsibilities—a new child, a parent needing support, a sibling or partner with health issues

playing a role in new change initiatives that are added to an already busy work schedule

At a moderate level of force, compression can feel stimulating. We figure out how to get things done more efficiently, come up with creative solutions, and learn how to delegate and collaborate. At high levels, we may feel overwhelmed, swamped, or at our limits.

Shear

Shear involves two pushing or pulling adjacent forces that cut or rip an object by sliding its molecules apart sideways. Inside, molecules hold on to each other to resist this movement.

Changes create shear when they lead to sudden or dramatic shifts in conditions or expectations. Here are some things that might lead people to experience shear:

being laid off from a job, being promoted, or moving to a dramatically different role

experiencing the unexpected death of a loved one or close friend

involvement in reorganizations or mergers requiring relocation to a new living situation

At moderate levels of force, shear can feel exciting, giving us the thrill of encountering something completely new and different. We recalibrate priorities, throw ourselves into new ways of being, and embrace unfamiliar experiences. At high levels, we may feel blindsided, disconnected, uprooted, and lost.

Torsion

Torsion involves a twisting force. It’s similar to shear, but at an angle rather than straight on; the twisting action produces shear stresses inside the material.

Changes create torsion when they alter significant aspects of work; redefine core values, norms, or mindsets; and ask people to direct efforts toward different objectives. Here are some things that might lead people to experience torsion:

Learning new skills that change how we do our work

Operating in a significantly different physical setting

Adjusting to a different set of criteria for evaluating performance

At moderate levels of force, torsion can feel playful and fun. We can try new perspectives, move in unfamiliar ways, and bring in fresh energy.2 At high levels, we may feel like we have lost our bearings, and be unsure which way to turn—all tied up in knots and confusion.

Bending

Bending occurs when a load is applied to an object that is fixed at both ends. One side compresses and the other side stretches.3

Changes create bending when pressure is felt from “the middle” of a situation—a force in one area pushing us to make adjustments in other areas. This is most common when dealing with budgets, time allocations, and other “fixed” situations where increased emphasis on one area requires decreased attention to other things. Here are some things that might lead people to experience bending:

dealing with increased costs or new budget priorities

making resource tradeoffs across multiple initiatives

pressure to increase performance in a particular area without increasing resources

At moderate levels of force, bending feels like the normal give and take of activity in the world. We experience fluidity and motion, with pressure in one direction usually being followed by a sense of release and new pressure from another source. However, when pressure from a particular direction is overpowering or enduring, we can feel bent out of shape, pushed, or buckle under the strain.

Strength

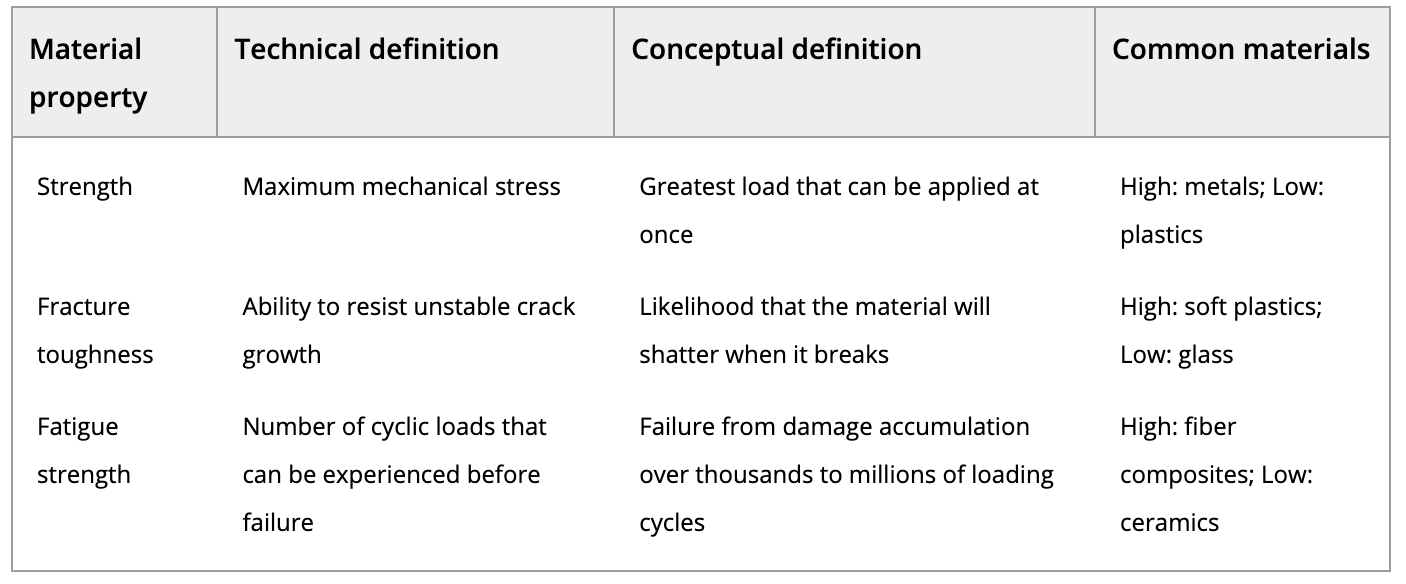

In looking at change from this perspective, I came across one last insight worth sharing. An interesting article on bone strength introduced three different ways of looking at fracture resistance drawn from engineering:

I think this has implications for humans as well. The factors that influence how much load we can take at once, how likely it is that we will shatter when we break, and how many cycles of demand we can take before we wear out are probably all different. Definitely some food for thought in my studies of resilience.

I hope this foray into materials science and bone strength has given you some interesting ideas to explore. As you plan, lead, and implement changes, what kinds of forces will they place on the humans involved? What kinds of forces are you experiencing in the present moment? Too much? Too little? Just right? How would you describe your own levels of strength and fracture resistance?

See you in two weeks for another installment of OCI!

An interesting article on the mechanical loading of bone.

Information on exercise for bone health.

I can’t help but think of twisting poses in yoga as a metaphor here…those feel so good to my spine!

One image I have is of books on a shelf that is bowed from not being strong enough to bear the weight over time.