OCI #18: Games People Play—Part 1

I'm OK / You're OK: Organizational change insights from Transactional Analysis

In the late 1950s, psychotherapist Eric Berne introduced a model of human relationships that he called Transactional Analysis (TA). His book Games People Play, originally published in 1964, brought the model to a wider audience. Although TA was based in part on the work of Sigmund Freud, it focuses on interactions between people (rather than what’s going on within the psyche) as its primary area of interest. I’ve always liked the model, and think it has some important implications for work in organizations, so I thought I’d provide a brief overview and discuss some of the insights I find particularly interesting.

Parent, Adult, Child

Transactional analysis starts with the idea that we can identify three different states people can embody as they relate to others1:

Parent—behaving, feeling, and thinking in ways we have seen parents or parental figures act; this can include both generative (nurturing, permission-giving) and critical (bossy, judgmental) manifestations

Adult—operating in a way that steps back and takes an objective perspective on reality; this is the state that is typically seen as the most balanced and healthy

Child—behaving, feeling, and thinking similarly to how we did in childhood; this can include a range of emotional responses (tears, yelling, laughter, spontaneity, joy)

When two people are relating to each other, the combination of states they are operating in affects the nature and effectiveness of the “transaction.” For example, you can imagine an exchange (1) in which a boss is in Parent mode with an employee, and the employee is in Child mode, and another exchange (2) in which both parties are in Adult mode2. These are both examples of “complementary” transactions, in which each person is sending certain kinds of messages and expecting certain kinds of responses, and the other person’s responses are fitting into the pattern.

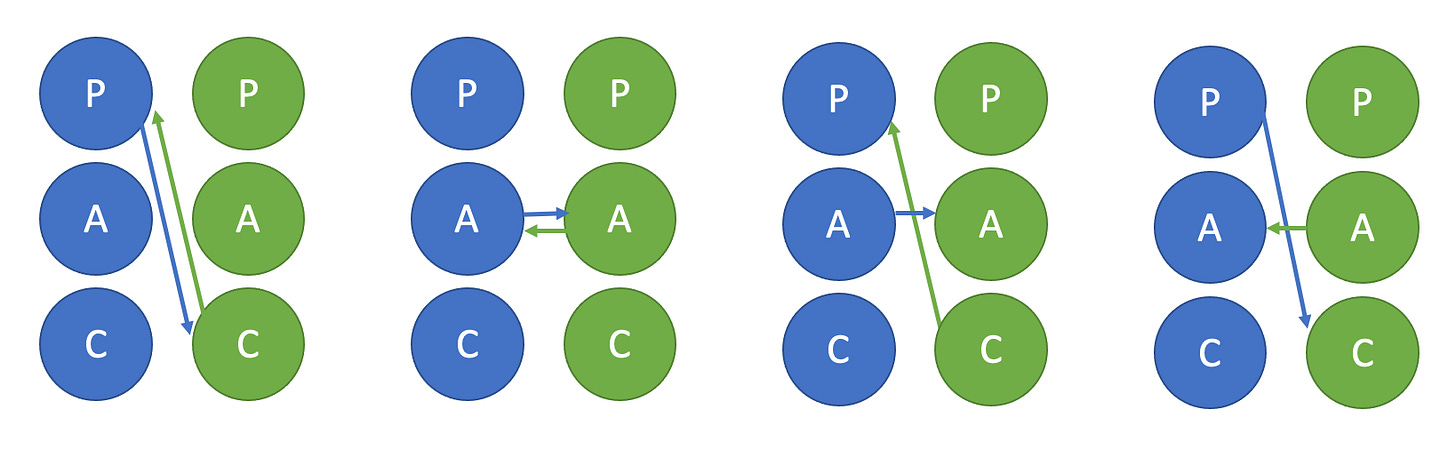

Transactions can also fall into patterns where the modes don’t match—for example, imagine an exchange (3) in which one person raises a concern by speaking Adult to Adult, but the other person responds as a Child, complaining that the first person is being mean; or an exchange (4) in which one person speaks as a benevolent (and possibly condescending) Parent, while the other individual does not take on the corresponding needy Child role but instead responds as a self-aware and responsible Adult. In these cases, one person or the other will tend to shift gears to bring the roles into balance. Patterns like these are sometimes called “crossed” patterns, based on the practice of diagramming interactions as a series of circles with arrows indicating the direction of communication. Here are examples from the four exchanges I described above.

Some transactions are healthier and more productive than others. To understand how this works, I need to introduce a second part of the model.

I’m OK, You’re OK

Berne also described four different perspectives an individual can hold about themself in relation to others.

I’m OK / You’re OK: I feel good about myself and about others and their capabilities. This is typically viewed as the healthiest stance.

I’m OK / You’re Not OK: I feel good about myself but see others as less strong, capable, or whole than me in some way. This can lead to a belief that is my job to fix, correct, or protect others.

I’m Not OK / You’re OK: I see myself as weaker, damaged, or less than others. This can lead to an overreliance on others and/or acceptance of abusive or controlling behavior.

I’m Not OK / You’re Not OK: I believe that all of us are weak, bad, or not doing well. This can lead to a lack of hope and possibility, and a willingness to give up too easily.

When people are operating from the OK/OK perspective, many kinds of healthy transactions are possible. My Child may speak to your Child and invite it to play. Our Adults may get together and build a plan to get something done. I may invite your wise Parent to mentor some aspect of my developing Child. However, the other combinations typically lead to less healthy interactions. I invite you to imagine some of the ways that the other perspectives might interact with the Parent, Adult, and Child modes to cause conflict and difficulty.

Implications for Organizational Change

Here are a few of the implications I see for leaders and agents of change.

Mode

When people are feeling uncertain, it’s very easy for them to slip into Child mode, looking for a Parent to help them. This can make it very easy for us to step into the complementary Parent mode, seeing ourselves as the people who have the answers. It’s typically a healthier response to move into Adult mode, speaking to them from a place of caring objectivity, to invite them to bring their Adult to the table as well.

It’s also very easy for some leaders to move into Parent mode as they attempt to influence others. At worst, this can lead to judging and berating people who aren’t doing what they want, but even with a relatively healthy mindset it can show up as an “I’m the boss of you” stance. This can hook the Child in their followers, and bring out behaviors that reinforce the leader-Parent mindset.

Perspective

Our models of change often encourage us to think of the people we are working with as obstacles or problems—the I’m OK / You’re Not OK stance. We speak in terms of resistance as something we need to deal with or manage, and we talk about all of the risks and problems that we need to overcome in the process. How might it look if we truly embraced the I’m OK / You’re OK stance—if we:

—trusted each person to bring their own insights and instincts and wisdom to the process

—believed that everything the organization needs to transform is already present within the system and that it’s our job to find it and liberate it

—focused our attention on the remarkable insights and curiosity people reveal when they face meaningful challenges?

I invite you to start noticing your own movement between the Parent, Adult, and Child modes, and begin to pay attention to how these ways of operating show up in the “transactions” you see. Where are interactions aligned? Where are they “crossed”? Healthy? Unhealthy? Which of the four (OK/Not OK) perspectives do you bring to the table most often? What do you see around you?

Our Role

Although we are not—and should not try to be—therapists, many of the insights and tools from transactional analysis can be applied to increase the level of helpful interaction in the system and decrease the level of confusion and conflict. In my next post I’ll talk about some patterns to pay attention to and an important tool for setting ourselves up for success.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this installment of Organizational Change Intersections! If you like it, I invite you to share it. See you in 2 weeks for Part 2 of this conversation.

I’m presenting the model in a very basic, plain-English way that necessarily loses some of the depth and psychological richness of the concepts. I invite you to read more deeply if you would like to explore further. I suggest you start with Thomas A. Harris’s I’m OK—You’re OK, or the updated edition of Eric Berne’s book Games People Play.

The three terms—Parent, Adult, and Child—are typically capitalized to indicate that they represent the “ego states” rather than actual parents, adults, and children. To clarify the distinction, think about times when you’ve heard a child talk like a Parent and an adult act like a Child.